Designing a narrative within a user-controlled world that is compelling enough for participants to easily follow the story arc was a challenge in our project to help players experience the social impacts of online hate speech.

Designing a narrative within a user-controlled world that is compelling enough for participants to easily follow the story arc was a challenge in our project to help players experience the social impacts of online hate speech.

Our team at the Department of Internal Affairs (DIA) conducted user testing early and often to identify the problems we needed to solve for the Online Social Norms VR tool.

About the Online Social Norms VR tool

The Online Social Norms VR tool is an immersive virtual reality (VR) experience that demonstrates how the digital environment amplifies and distorts content and experiences.

It aims to support communication and understanding about the impacts of destructive social norms, using hate speech as an initial focus.

The tool is being used by senior leaders and policy decision makers in NZ government to experience:

- what online hate speech looks like

- the perspectives of both the perpetrator and the receiver of online hate speech

- insights into the lives and motivations of people in these situations

- the significant impact online hate speech can have on people’s lives

- the destructive impact online disinhibition has on digital social norms.

This is the first time we’ve used VR to explore how emerging technology might inform policy development through structuring interactive storytelling within an immersive environment.

Immersive storytelling

Immersive storytelling is different from traditional storytelling in that the participant in VR can adopt the viewpoints of protagonists rather than just observe them.

The participant can also influence what happens by controlling what they look at, where and when they move, and which objects or characters they interact with. The experience can be different for each participant.

Using a headset and hand controllers to enter and participate in a virtual reality experience

The Online Social Norms VR experience

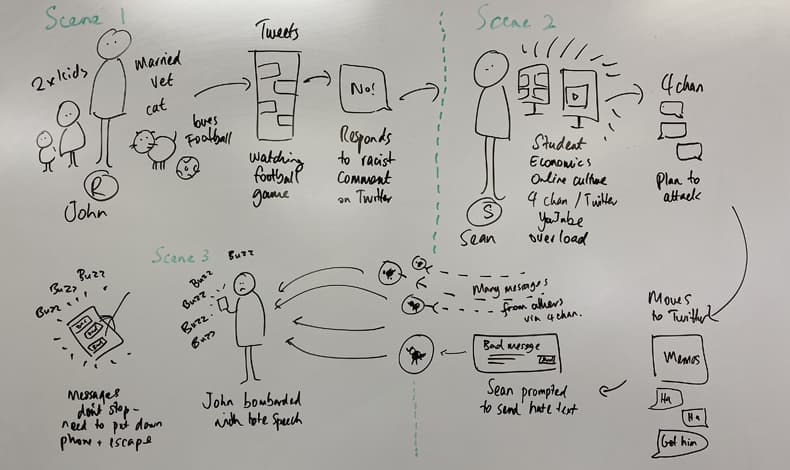

The story follows 2 main characters, the perpetrator, Sean, and the receiver, John, of the hate speech. They interact with each other online but have never met in person.

The player moves between the scenes — Sean’s bedroom and John’s living room — first observing each character from the outside, and then stepping in turn into each character to ‘become’ them.

Once assuming the role of one of the characters, the player is able to send and receive online messages through the avatars’ devices, using different social media channels.

The player moves between the perpetrator and the victim, experiencing being both the sender and the receiver of the hate speech.

By enabling the player to become both characters, they come to understand both sides of the story.

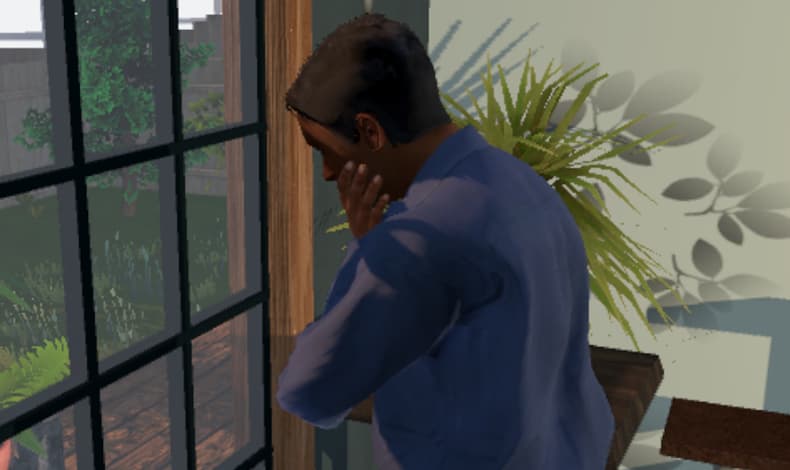

The player observes the character from the outside, then steps into the blue circle to become that character and experience the story from their perspective

User testing the early prototype

In August 2019, after building and assembling the test environment of the characters and 3D spaces, we began user testing the story in the VR experience.

The early prototype used geometric shapes to indicate the locations of characters and objects in the story.

We tested and iterated throughout the development of the tool, wanting to identify what made sense and what was confusing to the player. Test subjects were asked to ‘think out loud’ for the duration of the test experience.

Our 2 testers took notes of the players’ responses during the test sessions and we used these notes to synthesise the findings.

After each session, we spent a further 10-15 minutes with the test subjects, using a semi-structured interview to discuss their interpretations of the story, the characters and the online hate speech.

The user testing identified problems in the interaction design — these included players not understanding the storyline and characters.

Solving the challenges in the story arc

To make sure players had the intended experience and were able to easily follow the story arc, we developed a strong story line and characters, creating a distinctive ambience for each avatar’s world.

1. Story line

Early prototype

The test participants found the story superficial and confusing. They had difficulty in interpreting the story, which jumped around too much in time, and in understanding the relationship between the 2 main characters.

People questioned whether the 2 avatars were both in the same house, and if they were both ‘the baddies’.

This helped us identify that we needed to do a better job of the story sequencing of the VR experience.

Iteration after user testing

Linear story sequence

We remapped the story to a linear structure which made more sense to the player. This meant adding an extra scene. Testing confirmed players understood the story arc.

The story arc and character back stories were informed by evidence-based research

2. Characters

Early prototype

Test subjects found the characters shallow and clichéd. No one cared or connected with these characters, and with the story lacking warmth and depth the players felt little to no emotional engagement.

The test subjects also found it challenging moving quickly between 2 polar opposite characters to adopt their different viewpoints. This required the player to suddenly make a complete mental shift in perspective, but with these underdeveloped characters it made it hard for the players to feel the difference.

We understood we needed to find ways to build empathy and engage the players so that they connected more deeply with the characters and were able to switch perspectives more easily.

Iteration after user testing

We established a strong story arc with believable characters using 3 techniques.

Character backstories

We created backstories for each character, giving them names, families and personalities.

We added additional props in the VR environment to help reinforce the characters and the world they lived in. The décor and state of the rooms, and the objects in them, helped to give a clear sense of each character’s backstory without overstating it.

Sean, the character who sends the hate speech, is part of an online community that perpetuates and reinforces racist and inflammatory ideals

Visual cues

Using visual cues, we set the pace and timing of the social media messages the players send and receive when they became Sean or John — this was important for creating different emotional reactions in the player.

The cues guide player interactions and spark the build-up of online hate messages, causing the messaging to intensify and spread from 4Chan to expand exponentially on Twitter.

The player can scroll through the messages on forums resembling 4Chan and Twitter

Ambience

We created different ambiences for the times John received social media messages — conveying a relaxed state when he receives texts from friends and family, and a harassed state when he receives messages containing hate speech, showing his increasingly fearful reactions the more it intensified.

We did this by increasing the number and frequency of Tweets John receives on his phone — the experience is compounded through haptic feedback that makes the phone buzz and vibrate with each new Tweet. The avatar finds he can no longer access friendly messages from his family or business messages from his client because the phone is continuously displaying new Tweets with hate speech.

This helped build empathy in the player for John.

John, the character who receives the hate speech, has his life impacted on multiple levels

Further testing validated that players were interpreting these props and ambiences correctly and that this all helped the players connect with and understand the characters.

Players started to refer to their experience happening to ‘them’ personally rather than to the characters.

Research and application of hate speech

The story scenario, the characters, their actions, and the content of the hate speech messaging in the Online Social Norms VR experience is all informed by evidence-based research.

We took particular care to thread actual hate speech into a comprehensible story structure. The messaging needed to be genuine and use real-world examples to represent the language and terminology used in this context.

The research involved exploring and analysing sport forums, Twitter and 4Chan.

Examples of actual hate speech and racist memes were found using simple Google keyword searches.

We occasionally needed to make minor tweaks to the original messages to make them work within the flow of the story, but the majority of messaging has been left in its original form.

Safe speech version

We created a version of the Online Social Norms VR experience that uses 'safe speech' so that it can be used for educational purposes and demos for open audiences.

In the safe speech version we:

- created messaging that states the intention of the text, without using the actual hate speech

- replaced memes with representative colours and text

- customised video to reflect the intention of speech in the YouTube video rather than the content.

This means it's up to the player to make the leap to imagine what the text might be.

Read more about the Online Social Norms VR project

Read our first blogpost on the Online Social Norms VR project:

Exploring how government can use virtual reality for public good