Purpose Matters: Assess purpose and only collect what is needed

Agencies should assess the purpose of collecting personal information to ensure they are collecting only what’s needed.

If you have any questions about DPUP email dataethics@stats.govt.nz.

Assess the purpose for collection

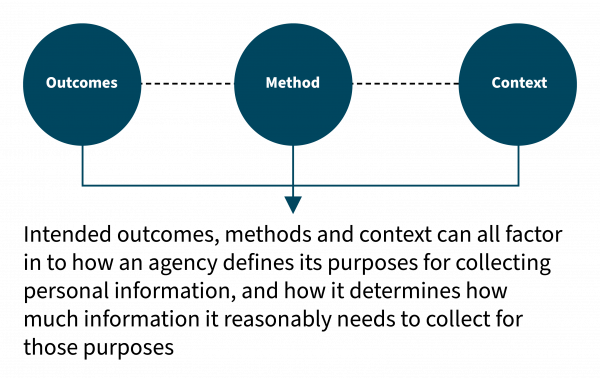

When assessing the purpose of collecting personal information and the kinds of information to be collected, agencies should:

- be clear about the outcomes to be achieved

- be clear about the method that will be used to achieve the outcomes

- consider in what context the information will be collected and used.

Detailed description of diagram

Diagram shows 3 circles labelled ‘Outcomes’, ‘Method’ and ‘Context’ connected by dotted lines pointing to the text that explains that these can all factor into how an agency defines its purposes for collecting personal information, and how it determines how much information it reasonably needs to collect for those purposes.

Clarity in these areas can help an agency to:

- formulate the purpose of collection

- assess if that purpose relates to the agency’s functions or activities

- assess what personal information is needed to achieve the outcome

- determine if the collection is ethically justifiable and aligns to respectful practice (even if it will tick all legal boxes).

Be clear about the outcomes

To have clarity of purpose it’s necessary to understand why data or information is being collected — that is, the outcome or result of using it.

This should be well-defined and easy for a range of people, including service users, to understand. It should be written down. Recording it:

- helps agencies to think clearly

- captures information that needs to be communicated to service users — either directly, if the collecting agency is collecting the information directly from services users, or through another agency that is collecting the information from service users

- provides the basis for the collecting agency to determine if proposed future uses or disclosures of the information are for a purpose it was collected for or a directly related purpose.

Without clarity, an agency may not be able to determine if it’s necessary to collect the information it proposes to collect. In that event, the agency’s collection may breach the Privacy Act 2020’s information privacy principle 1 (IPP1) — Purpose of collection of personal information or, where relevant, not fall within a specific statutory collection power the agency is aiming to use.

IPP1: Purpose for collection of personal information — Office of the Privacy Commissioner

Who the outcomes serve

When considering the outcomes, it can be helpful to reflect on who the outcomes serve:

- Do the individuals the information is collected from benefit, or do other people or does wider society benefit?

- If the benefit is to other people or wider society, what will the people providing the information think about that?

- Even though the Privacy Act 2020 or a specific statutory provision may allow the collecting, is using the information to benefit others ethically justifiable?

Be specific about what the information will be used for

Agencies need to avoid broad and ambiguous statements of purpose or outcomes. If your agency is collecting information for analysis, policy development or service design, either by itself or in conjunction with other data, you should describe these uses as precisely as possible.

If the results will be used to provide more targeted services and better outcomes for people, then say that, being as precise as possible.

If the results could lead to taking adverse action against people, say that too.

Consider telling people what their information will not be used for

IPP3 — Collection of information from subject — is concerned with telling people about the purposes for which their information will be used. That makes sense, especially when other uses are not permitted unless either an exception in IPP10 — Limits on use of personal information — applies or a separate statutory provision authorises another use. However, agencies cannot expect service users to understand this legal position.

- IPP3: Collection of personal information from subject — Office of the Privacy Commissioner

- IPP10: Use of personal information — Office of the Privacy Commissioner

It can sometimes be helpful to explain to people that, while their information will be used for purposes A and B, it will not be used for purposes X or Y. For example, if your agency is collecting particularly sensitive information about people to provide them with immediate care, and there’s no intention to allow any identifying information to be seen by researchers or other agencies, you could say that.

Similarly, if the information you’re collecting includes unique identifiers like a driver licence number, IRD number or passport number, you might want to tell people their number will not be used to match information you have about them with information another agency has about them. Deciding if it’s a good idea to make statements like this will depend on the context.

This consideration can be particularly important where people may fear their information will be used in a prejudicial manner against them. Taking this approach can help increase people’s levels of comfort with what’s happening with their information.

Be careful with evolving purpose statements

When a policy, service or programme is evolving , an agency may change or refine how it articulates the purpose of a proposed collection before collecting the information. If so, the agency should:

- be clear about which purpose statement is the final one

- state if the final statement is intended to replace earlier explanations.

Having different explanations of the purpose of collection across different policy, service or programme documents can lead to confusion about what the actual purpose of collection is or was. This could result in errors when explaining to people why the information is being collected and how it will be used.

It could also result in service users losing trust in the agency. If there is cause for an investigation into the purposes of collection, different purpose statements over time could result in uncertainty and adverse findings.

Be clear about the method

Why the method is important

As well as having a clear understanding of the outcome, it’s important to consider the method to achieve the outcome. Both the end and the means are important.

Knowing how the information will be processed to achieve the outcome can be relevant to determining if the information being collected can or will contribute to the outcome and, therefore, whether all of it is required to achieve the outcome.

An application form for a service might collect personal information such as a person’s name, date of birth, annual income, address, gender and ethnicity.

However, a tool to process such applications, and designed to match the eligibility criteria for the service, may only need name, date of birth, address and annual income.

The agency may have no plans to use the information relating to gender and ethnicity. In that kind of situation, collecting information on gender and ethnicity would be unnecessary and, in all likelihood, unlawful.

Consider different analytical techniques or processes

In some situations, there may be different analytical techniques or processes for achieving an outcome. To achieve the outcome, the different techniques or processes may require more or less personal information, or even no personal information at all (because, for example, it can be de-identified before collection).

If one technique requiring less personal information can easily be deployed over another that requires more personal information, respectful practice means choosing the former technique to minimise the amount of personal information collected.

If a collecting agency needs to know people are over 20 years of age, it might use a tool that asks for a person’s date of birth or age but then uses that to work out if the person is over 20 and only stores a ‘Yes over 20’ response, instead of the date of birth or current age.

Collecting agencies that need help with this can reach out to others with relevant experience or expertise. Depending on the context, it might be helpful to seek advice from other agencies such as Stats NZ, frontline non-governmental organisations (NGOs), service user representatives, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner or the Government Chief Privacy Officer.

Should agencies collect personal information from every service user all the time

In some situations, an agency may propose to collect information from a wide group of people to achieve a stated purpose or outcome. However, the group may have different subgroups or be made up of people with different service needs, sensitivities or fears.

At a macro level, it may be reasonable to conclude that it’s reasonably necessary to collect personal information from members of the wide group of people to achieve the stated purpose. However, it does not necessarily follow that the information needs to be collected from every member of the group, all the time, and regardless of individuals’ different service needs, sensitivities or fears. That depends on the context.

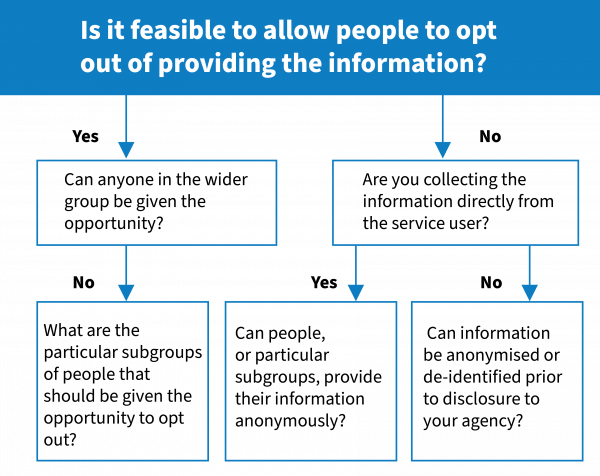

The key point is to consider whether the purpose can be achieved if only a proportion of people in the group provide the information requested. If the answer is yes, it may be helpful to assess whether allowing people to opt out of providing the information is feasible. If it is, the collecting agency can then consider whether anyone in the wider group should be given this option or whether there are particular subgroups of people, for example, vulnerable people needing services for particularly sensitive issues, that should be given the opportunity to opt out.

If opting out is not feasible, another option might be to allow people, or particular subgroups, to provide their information anonymously. Or, if the collecting agency (Agency A) is collecting information from another agency or organisation (Agency B) that collects personal information directly from individuals, it may be possible for Agency A’s purposes to be achieved by collecting information from Agency B that has been anonymised or de-identified prior to disclosure to Agency A.

Detailed description of diagram

The diagram is a flowchart that starts at the top with the text on a blue background: “Is it feasible to allow people to opt out of providing the information?” From this text, 2 blue arrows point downwards representing 2 options ‘Yes’ and ‘No’. The first option / arrow with the word ‘Yes’ against it points down to a box containing the words: “Can anyone in the wider group be given the opportunity?” From this box, a blue arrow with ‘No’ against it points downwards to a box containing the words: “What are the particular subgroups of people that should be given the opportunity to opt out?”

From the top text box, the second option / arrow with the word ‘No’ against it points down to a box containing the words: “Are you collecting the information directly from the service user?” Two blue arrows point downwards from this box representing the options, ‘Yes’ and ‘No’. The first option / arrow with the word ‘Yes’ against it points down to a box containing the words: “Can people or particular subgroups, provide their information anonymously?” The second option / arrow with the word ‘No’ against it points down to a box containing the words: “Can information be anonymised or de-identified prior to disclosure to your agency?”

When IPP1 applies, these considerations are directly relevant to whether the collecting agency can conclude that it’s always reasonably necessary to collect the personal information from everyone, all the time.

The wider and more diverse a group is, or the longer the period of information collection is likely to be, the more important this question may become.

If agencies collect information from one channel or into 1 repository

Sometimes agencies collect different kinds of personal information for different purposes but through a single collection channel and into a single location. In other situations, an agency might use different collection channels but collate all the information into a single repository or output, such as a spreadsheet.

If there are several groups within an agency who need to have access to different kinds of personal information, having all the information in 1 location or repository could result in some staff having access to personal information they do not need to see and which, therefore, they should not see.

This could also be contrary to IPP5 — Storage and security of personal information. Under IPP5, agencies need to ensure that personal information they hold is protected by reasonable security safeguards “against ... access, use, modification, or disclosure that is not authorised by the agency”.

In this kind of situation, part of the method for achieving the outcomes (that is, the means for collecting and collating the information) may be inappropriate and needs to be reconsidered. This can be particularly important as service users can get understandably worried about too many or the wrong people having access to their personal information.

IPP5: Storage and security of personal information — Office of the Privacy Commissioner

Consider the context

Relevance of context

Context matters because it influences how people might feel about the collection or use of their personal information for particular purposes or how much information is collected, and that, in turn, may affect their wellbeing.

It also affects the kinds of checks and balances an agency may decide to work through before collecting, using or sharing personal information for a particular purpose — especially if there’s any risk that collecting, using or sharing personal information in the manner proposed could do, or be perceived to do, more harm than good.

Context can also be relevant to the collection, use or sharing of information that has been de-identified, in the sense that it will not be possible to identify specific individuals from the de-identified information. This is because de-identified information can still contain information that some individuals, groups or cultures may find sensitive.

It can be particularly important to remember that, while the Privacy Act 2020 is concerned with the privacy of individuals, we live in a society where broader groups have legitimate privacy interests.

The Privacy Act 2020’s controls may fall away once personal information has been fully de-identified in the sense described above, but the remaining information could still be sensitive to, for example, whānau, hapū, iwi, Māori, other cultural groups or other societal groups.

The next part of this Guideline provides guidance on potentially relevant contextual matters and describes some specific issues that may be particularly important in some situations.

Questions to consider

The following are some contextual matters to consider in decision-making.

Utility links and page information

Last updated